The Most Beautiful Film Ever Made. Full Stop.

It’s nice to have smart friends.

One of the first films I ever worked on was a short film that I shot for a friend and his wife about a small town in the Dominican Republic. My friends were guests on a well-known television quiz show at the time — The $25,000 Pyramid — and they won. They decided to use the windfall to fund a documentary.

The film they decided to make was to be about a small community of Jewish immigrants who had been allowed to come to the Dominican Republic during the Second World War. The island’s president, Rafael Trujillo — famous for human rights abuses — agreed to allow refugees to come to his island believing, it has been suggested, that he would get favors in return from the United States.

Trujillo’s caveat was that the Island’s new citizens had to be sent to an isolated, totally undeveloped part of the island. These new arrivals, mostly Germans and Austrians, were well educated and came from professions and the arts. They were teachers and writers and business owners and musicians. They arrived with little more than the clothes they were wearing and suddenly they found themselves thrown into a Spanish-speaking tropical climate with no recognizable way of making a living in sight. Mostly, they became farmers even though many of them had never even seen a cow up close.

After a few years of struggle, they learned how to survive raising cattle like everyone else out there. They built homes. And they inter-married with Dominican locals. In short time, they set up a collective that came to be the biggest, most successful cheeze business on the island.

We went to document their story. The town and the resulting film was called Sosua.

You call this work?

This was the first time I’d been hired to go somewhere outside the U.S. to make a film. And, boy, was it an amazing experience. From the first instant being there, I never wanted to do anything else in life. I assumed that all future shoots would be this satisfying — even if there wasn’t a similarly built-in swim in the warm ocean at the end of each day.

Since I was the only person on the tiny crew who could speak Spanish — I’d learned while in the Peace Corps in Chile — I got used to acting as the translator and being a kind of bridge between the producers and the Dominicans. And, since I had never gone to any sort of film school where they taught proper set etiquette, I just assumed that my job description as the cameraman included being deeply involved in all decisions that needed to be made. I went for years and years assuming that this was standard operating procedure for a cinematographer on a film. And without knowing it, I began to develop a reputation for being much more than the guy who just shot beautiful images, but also for being a emersive collaborator-kind-of-guy with good ideas to boot.

After the shoot was over and we were back in New York where I was living at the time, we started editing the film at a small edit house in midtown Manhattan. That phase of the project was equally as wonderful — in its own way. Watching the film come together in the editing process added more magic to the already-existing magic from the shoot. So, while I was already permanently hooked on making films up to that point, I was now doubly in love with the entire process.

John Mullen, the owner of the editing house, generously introduced me to the editors working on other films being cut in the building and they allowed me to hang around and watch them work. In another editing room on the same floor, they were putting together a documentary film about Leonard Crowdog, a Medicine man and spiritual leader of the Sioux Indians. A couple of days each week, the director of the film named Mike Cuesta would come in and give the editor his “notes.” I learned more just sitting there and listening to him than I could have learned in an entire year of film school.

Heaven On The Cutting Room Floor

In the “big” edit room, John was cutting a trailer for theatrical film that had been shot on 35mm film. Each frame, a little more than an inch and a half wide, was more than twice the size of our film that was shot on 16mm. What a difference to be able to really examine every single frame up close. I had never seen images so beautiful. And I’m not sure I ever will again.

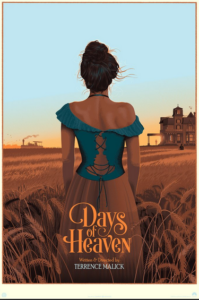

The film was called Days of Heaven and was directed by a relatively unknown filmmaker named Terrence Malick. Watching the trailer being edited together every day was better than having a 6 course meal served in bed. Seeing the film in a movie theater was dazzling. Without realizing it, I wandered out into the sunlight a different person. For years and years to come, I walked around with a few of the images that I literally picked up off the editing room floor that I carried safely in a dedicated side pocket of my backpack in a protective white envelope.

The majority of the shots from the film were photographed outdoors during what I learned was referred to as “magic hour,” that small window of time at the end of the day when the sunlight gets most beautiful. In the end, the film wasn’t considered a commercial success: maybe because it was slow paced and thoughtful.

Occasionally, over the years, I’ve given short demonstrations and classes to film students about the craft of cinematography and I never fail to bring out the sacred envelope with those breathtaking images inside. And as they held up the clips to the light as I had often done, I would talk about the discipline that Terry and his crew went through to get such heart stoppingly beautiful shots.

I wasn’t alone. The Village Voice called Days of Heaven, “the most gorgeously photographed film ever made.” The film, shot by Nestor Almendros and Haskell Wexler, went on to win an Academy Award for Best Cinematography.

CUT TO

Almost twenty years later

A phone call gets through to me at hotel in Italy where I am working. I expected it to be the producer with whom I was going to have dinner that night.

The voice clearly wasn’t that of the producer. “Hi, I’m calling from Terence Malick’s production office in Los Angeles and we wanted to speak with you about a feature film project we are shooting later in the year.”

I pantomimed the cliche, “You could have knocked me over with a feather.”

Wait: Terry is alive? Wait: Terry is making a new film? Wait: you’re calling me long distance about helping in some way?!!!

Are You kidding me???

After getting past the initial shock plus the part where I picked myself up off the floor, I came to realize that the call wasn’t a prank from one of the documentary crew members with me in Italy. I collected my composure and carried on what was a very one-sided phone call what with me caught almost speechless.

“Yeah, I think he was interested,” the caller must have concluded. “But that Aaronson guy sure doesn’t talk a whole lot.”

What I gathered from the brief call was that he was making a film based a novel called The Thin Red Line by James Jones about the battles between U.S. and Japanese during the Second World War in the Solomon Islands. The production company had apparently found me through my friend David McKillop, the production manager at National Geographic who recommended me to them as someone who might be able to help them get images that he was hoping to get.

Through the fog in my brain, I was able to understand that they were looking for someone with my skills to form a kind of second or maybe a third unit to get images of the native people and natural history of the island. Terry wanted this unit to work separately from the main shooting unit that would be working at the same time but in Australia. He wanted me to find people still living in their traditional ways, to live with them long enough to gain their trust and bring back beautiful images of their world.

A few very long months of waiting later, they flew me out to LA for an interview with the executive producer, George Stevens Jr. and with Terry himself and with the Director of Photography John Toll who just the previous year had won an Academy Award for Cinematography for the film Braveheart. We met at one of the production offices at 20th Century Fox in Hollywood. After the meeting, I showed John the still from the editing room floor.

If you wonder if it was a dreamlike experience for me… you bet it was. And, wait, did I just call him “Terry?”

I returned to D.C. the next morning still in a daze. I went on with my world of documentary filmmaking back home, but never being more than 6 inches away from a phone — just in case they might call to confirm that I’d gotten the job over who-knows-how-many-other infinitely more qualified blokes than me that they were interviewing for the position.

To Be Continued…

![]()

![]()