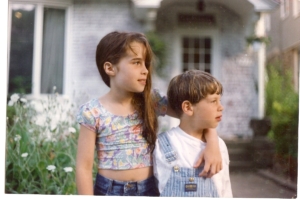

That’s Sophie on the left who called me a Filmer.

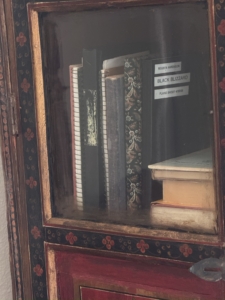

There’s a red wooden cabinet in my office that I shipped home from India at the end of a film project there. On its top shelf sit a couple of dozen journals—remnants of my ongoing attempts over the years to record what happens on a daily basis working on documentary films around the world.

I began keeping these journals with a specific purpose in mind: to share the realities of my work with those closest to me. My father often expressed curiosity about what I did “out there,” and my young children who were too little to grasp the nature of my travels and projects. My oldest child Sophie called me a “Filmer.” These notebooks became a bridge—a way to convey the experiences, challenges, and moments that defined my time away from home. You know: doing whatever a Filmer does.

Some of these notebooks go way back. Flipping through them reminds me not just how long I’ve been at this work, but how hard it’s always been to maintain a daily journal while navigating the unpredictability of filming on location. There are entries from a week-long death ritual in Borneo, a shoot with the Korowai people of Irian Jaya who build treehouses high in the rainforest canopy, the construction of a gondola in Venice by the last man considered a true master of the trade, and a look behind the walls of the world’s oldest institution-the Vatican.

Many of these journals have more blank pages than filled ones. But what’s there matters: wonderful reminders of the ups and downs and the little details of what it means to be a Filmer. Details otherwise lost to the new details of the next project and the next.

Every new project begins with enthusiasm for keeping a completed journal, that I’ll have time and energy left at the end of each day to write. But inevitably, a few days into the shoot, jet lag wraps around me like gravity. The day’s work is so consuming that I often fall asleep before even reaching the bed. Or only manage a few words put to paper.

Still, scattered through the pages are small details and insights that are wonderful.

In one journal from Borneo where we were documenting a community-wide, week-long ritual celebration burial, I came across these scribblings in my terrible handwriting:

Interview Bapap Luow re his buffalo at the river’s edge.

Followed by

Buffalo goes down the street B.L. leads, ties to post. Then again shot at 6fps. Moon.

Followed by

Sacrifice buffalo

pigs speared

dancing

chanting ritual

Notes reminding myself that we used the dolly later to film the head priest thru a thick cloud of burning incense.

In another notebook—from a shoot in Bangladesh about man-eating tigers—I scribbled about the strangeness of arriving with our white faces and black cameras.

It’s as if we are aliens to them with our white faces looking through black boxes.

People think documentaries are always about capturing what’s real. but a question that will return often in these pages is just what is real? If we film a long interview, but edit it down to 30 seconds, what have we left out? Why?

We see women in town walking in flowing sairs. I get the idea to film a few of them up on the ledge that overlooks the river there (where many of the fishermen of the village have been killed).

As usual, it took what seemed like forever to accomplish what would be easy in a different culture. After we describe the shot to our translator, he explains to them — you three women walk from that tree to the bend in the river. “no we carify, not that tree, that other one.” The back and forth takes seemingly forever. By then a crowd of villagers encircles, forever curious about the conversation, they look on with concerned, childlike eyes, speaking quietly between themselves.

We gently ask, ‘Please don’t look at the camera as you walk. Talk with each other if you like.’ Filmmaking 101.

The three beautiful women eventually agree, cautiously stepping up to the tree while what seems like the entire village now watched from behind our camera. (With the exception, of course, of countless children and animals who go unrestrained or controlled.) Delays continue because the women find our request to be extremely odd for many reasons. ‘Why walk up there there? We never do: there could be a tiger. And, besides, we’re not going that way.’ There’s laughter. Some of it was nervous, some of it shared.”

Classic filmmakers might frown at us messing with reality here. Why not just film them walking around naturally on, say, a long lens so they don’t even know they’re being filmed? Are we crossing a line here by manipulating the scene? The slight breeze above along the pathway next to the river will make their suris flow beautifully, and the river itself is there where many of the tiger attacks have made them widows. Who knows, this could be an opening shot to the completed film.

Throughout it all, laughter, universal and disarming, helping to carry us through countless awkward moments here and in foreign lands everywhere.

I was lucky. The “interesting projects” (as my dad used to call them) just kept coming. And, even if most of my journals remained half-empty and scrawled in my barely legible handwriting, I’ve never given up the hope of recording what it’s really like to make films like a Filmer—to catch, on paper, some part of what the experience feels like.

What happens during these projects—the camaraderie, the interactions with local people, the daily hurdles and discoveries, the reflections about self and place—are what make my work so deeply compelling. Even addictive. Some of those memories are in the journals. Others return through photos or rewatching the finished films. Mostly, those memories are sadly gone.

This website, Journals on My Shelf, is a way to gather those fragments—a simple recounting of lessons learned from a life of making films. Part travelogue, part filmmaking guide, part personal journal. It’s an insider’s look at what it means to try and tell real stories a long way from home as well as a way to look back on what my work over a lifetime has meant to me.